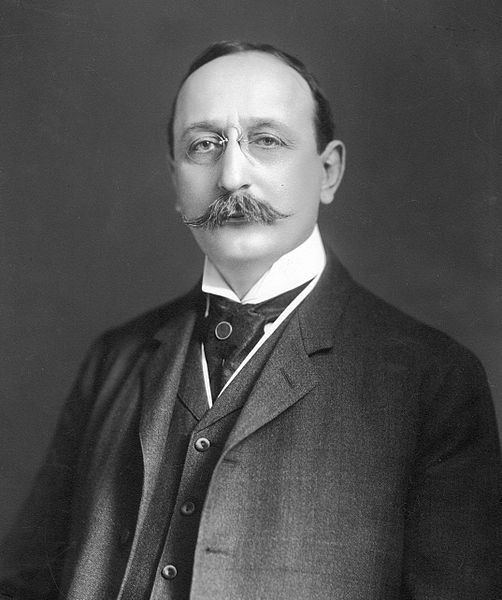

Babe Ruth has a couple of things in common with Cass Gilbert, architect of the Broadway Chambers Building. Both were superstars in their field, and both came to New York via Boston. (But Cass Gilbert came 20 years ahead of the Babe.) *

According to the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, St. Paul, Minnesota-based Gilbert became prominent for his 1893 design of the Minnesota State Capitol. That led to an 1896 commission to design a commercial building – the Second Brazer Building – in Boston. Alexander Porter, an investor in that project, was so impressed with Gilbert’s work that he introduced him to Edward Andrews, who happened to be looking for someone to design a new building on Broadway at Chambers Street.

The resulting Broadway Chambers Building, begun in March 1899, was Gilbert’s first project in New York. It was immediately successful – and followed by nine other architectural landmarks by 1936. (Babe Ruth’s career closed in 1935.)

Like other tall buildings of the era, the Broadway Chambers Building was designed like a classical column, with base, shaft, and capital. Gilbert used the then-popular Beaux Arts style of ornamentation, with a twist dictated by Andrews: Color, to make the building stand out among the monochromatic neighbors.

The three-story base is of pink granite; the 11-story shaft is of red and blue brick; and the four-story capital is of beige terra cotta with blue, green, yellow and pink accents, and a green copper cornice. The base and crown are deeply rusticated (the joints between the blocks of granite or terra cotta are deeply incised). The brickwork of the middle floors has bands of raised brick that mimics (in reverse) the rustication.

While the Broadway Chambers Building was Cass Gilbert’s first New York project, his most famous building was erected three blocks south and 13 years later: The Woolworth Building (celebrating its centennial in 1913). Gilbert’s other New York City landmark buildings include: United States Custom House (1907), 90 West Street Building (1907), Rodin Studios (1917), New York Life Insurance Company (1928), 130 W30th Street (1928), Audubon Terrace auditorium and art gallery (1928), New York County Lawyers’ Association (1930), and United States Courthouse (1936 – completed after Gilbert’s death in 1934).

* OK, I know I just gave architects and architectural historians massive heart attacks by coupling a great architect with a mere baseball player. I accept that I am forever banned from the Society of Architectural Historians and the American Institute of Architects. But this is a website aimed at non-professionals.

Broadway Chambers Building Vital Statistics

- Location: 277 Broadway at Chambers Street

- Year completed: 1900

- Architect: Cass Gilbert

- Floors: 18

- Style: Beaux Arts

- New York City Landmark: 1992

Broadway Chambers Building Suggested Reading

- Wikipedia entry

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report

- Daytonian in Manhattan blog

- Cass Gilbert Society listing

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5401 11/20/2012 9:19:34 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5401 11/20/2012 9:19:34 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5401_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5432 11/20/2012 9:40:29 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5432 11/20/2012 9:40:29 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5432_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5510 11/20/2012 10:30:01 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5510 11/20/2012 10:30:01 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5510_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5522 11/20/2012 10:37:45 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5522 11/20/2012 10:37:45 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5522_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5533 11/20/2012 10:44:25 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5533 11/20/2012 10:44:25 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5533_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5538 11/20/2012 10:47:35 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5538 11/20/2012 10:47:35 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5538_resize.jpg)

![[Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5547 11/20/2012 10:51:17 AM [Thurgood Marshall Courthouse] IMG_5547 11/20/2012 10:51:17 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/thurgood-marshall-us-courthouse/i_5547_resize.jpg)

![[90 West Street Building] IMG_6480 12/28/2012 10:33:26 AM [90 West Street Building] IMG_6480 12/28/2012 10:33:26 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/90-west-street/IMG_6480_resize.jpg)

![[90 West Street Building] IMG_3966 10/18/2012 3:16:22 PM [90 West Street Building] IMG_3966 10/18/2012 3:16:22 PM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/90-west-street/IMG_3966_resize.jpg)

![[90 West Street Building] IMG_6467 12/28/2012 10:29:08 AM [90 West Street Building] IMG_6467 12/28/2012 10:29:08 AM](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/90-west-street/IMG_6467_resize.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.