51 Astor Place, scorned as the “Death Star” of Greenwich Village, is an imaginative form for the irregular former site of Cooper Union’s engineering school.

The Village Voice‘s harsh words may be familiarity-bred contempt. The Voice was headquartered just two blocks south during the years of construction.

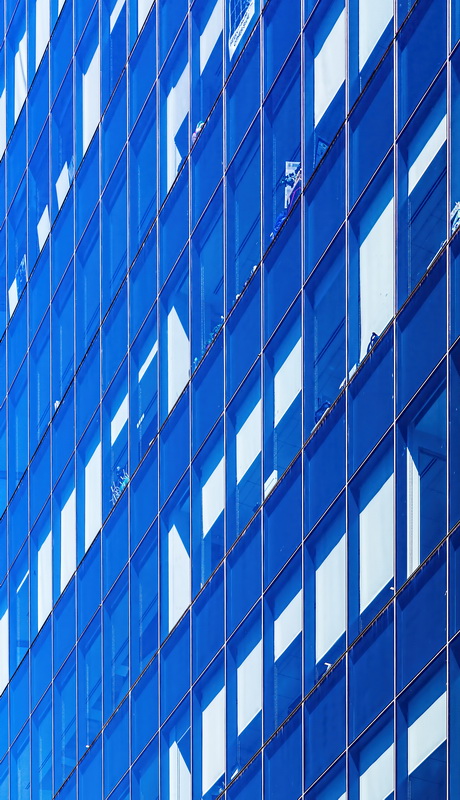

Certainly, the blue-black mirror-glass edifice towers over and clashes with most of its low-rise masonry landmark neighbors. Paradoxically, the reflective facade makes the 1906 landmark Wanamaker’s Annex twice as prominent.

Viewed from the west, the Fourth Avenue facade seems simple a simple monolith, like a giant tower PC. (A fitting image, as the prime tenant is IBM!) From any other angle, the irregular pentagon takes on more complex forms. The east side of the tower incorporates an optical illusion. The wall is split diagonally into narrow panes of light-colored glass above wide panes of dark-colored glass, giving the appearance of a faceted facade. The view from above (via Google Earth) is revealing.

The eastern side of the building – with separate entry numbered 101 Astor Place – is now the Manhattan campus of St. John’s University.

Meanwhile, Architect Magazine explains why and how the Third Avenue and Fourth Avenue facades are different. The Metals in Construction article explains the building’s complexities.

51 Astor Place Vital Statistics

- Location: 51 Astor Place: block bounded by E 9th Street, Third Avenue, E 8th Street, Fourth Avenue

- Year completed: 2013

- Architect: Fumihiko Maki

- Floors: 12

- Style: Postmodern

51 Astor Place Recommended Reading

- The New York Times A Sleek Office Building Rises Over Gritty Astor Place (March 26, 2013)

- The Real Deal listing

- Architect Magazine project page

- The Village Voice Will Success Spoil Astor Place? (March 5, 2014)

- Metals In Construction 51 Astor Place (Fall 2013)

- Emporis database

- St. John’s University The Torch Manhattan campus relocates to 51 Astor Place (December 19, 2013)