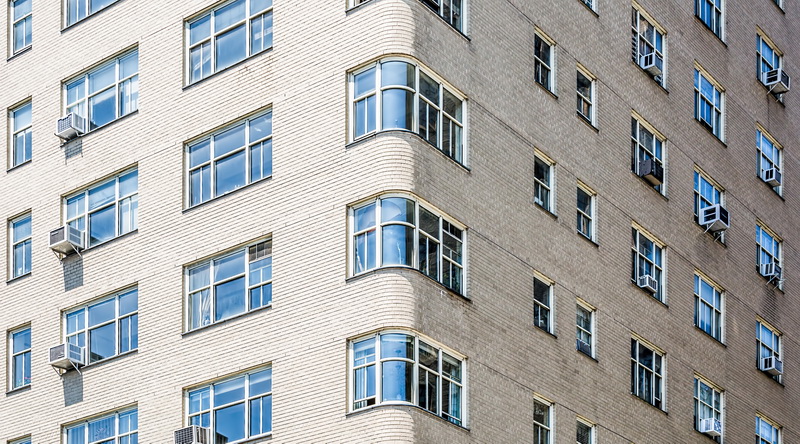

Fish Building is “one of the most astonishing apartment houses in the Bronx, indeed in New York City,” wrote Christopher Gray in his July 15, 2007 New York Times Streetscapes column. The six-story building, aka 1150 Grand Concourse, is an Art Deco delight designed by Horace Ginsbern and Marvin Fine. This Grand Concourse landmark gets its name from the aquarium motif mosaic at the main entry.

But Mr. Gray decries the structure’s decline. “HOW do old buildings disappear? Sometimes all at once, under the wrecking ball. But more often they fade away on little cat’s feet, first the cornice, then a doorway, then the windows, then a balcony … leaving behind nothing but an architectural zombie.” And indeed, historical photos that accompany the Streetscapes column show an even more fantastic Fish Building existed some 50-odd years ago. The original cornice, roof railing, windows and door have been replaced with unimaginative substitutes.

Clever Design

At least one aspect of the building’s design is permanent: Its adaptation to the irregular street grid.

The Grand Concourse was designed as a scenic boulevard, and as such it meanders to follow the terrain, often at an odd angle to the street grid. Such is the case at Mc Clellan Street. The Fish Building accommodates the boulevard’s zig with a stepped western facade that artfully hides the skewed grid, and keeps apartment walls rectangular. See the floor plans from Columbia University’s New York Real Estate Brochure Collection.

If the outside of 1150 Grand Concourse is exceptional, the inside is absolutely stunning. The terrazzo floor, murals, light fixtures and boldly decorated elevators are a joy to behold.

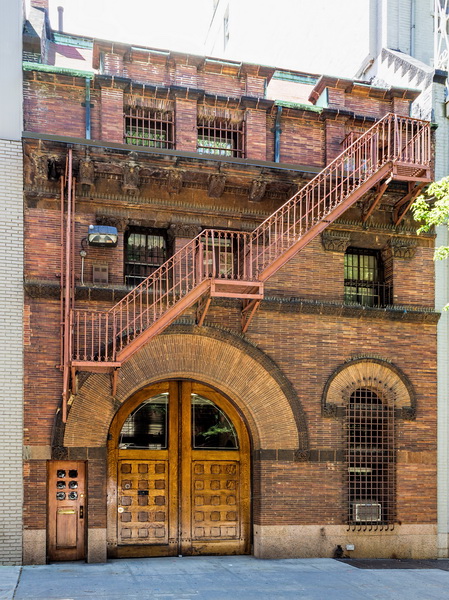

If the Fish Building leaves you wanting more, you can visit nearby Park Plaza Apartments. It’s located at 1005 Jerome Avenue, across the street from Yankee Stadium. This grander-scaled apartment building was also designed in Art Deco style by Ginsbern and Fine. It features bold, colorful terra cotta details definitely worth the trip.

Fish Building Vital Statistics

- Location: 1150 Grand Concourse at Mc Clellan Street

- Year completed: 1937

- Architect: Horace Ginsbern and Marvin Fine

- Floors: 6

- Style: Art Deco

- New York City Landmark: 2011 (Grand Concourse Historic District)

Fish Building Recommended Reading

Google Map