640 Broadway, designed by DeLemos & Cordes and completed in 1897, is the original Empire State Building – named for the bank that was housed on the ground floor.

DeLemos & Cordes would go on to design much grander buildings – notably the Keuffel & Esser Company Building, Siegel, Cooper & Co. Department Store, and the R.H. Macy & Co. Department Store at Herald Square.

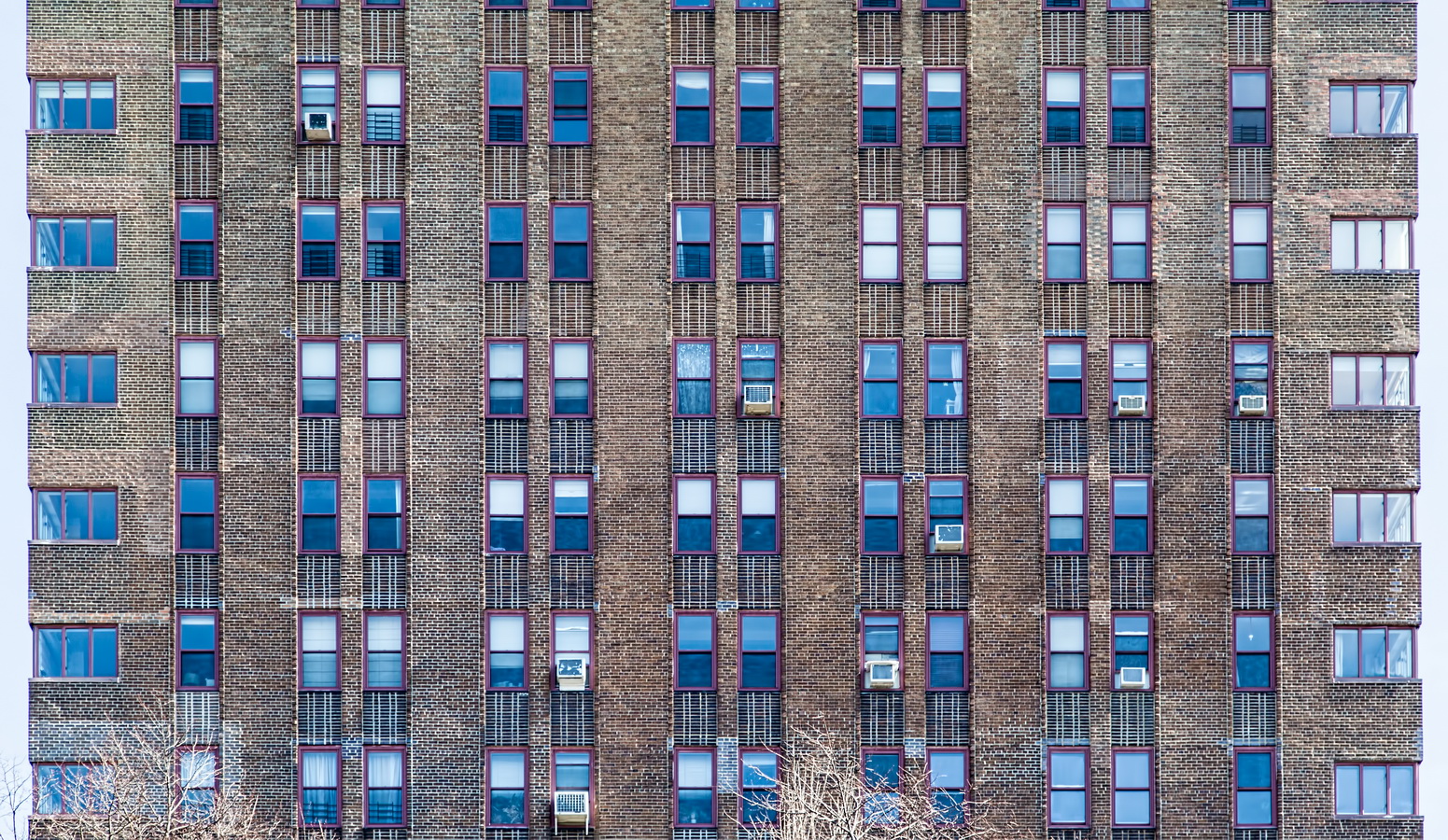

The building’s original commercial tenants – including the Empire State Bank – have long since departed; a Swatch store now occupies the ground floor; upper floors have been converted to loft apartments.

640 Broadway Vital Statistics

- Location: 640 Broadway at Bleecker Street

- Year completed: 1897

- Architect: DeLemos & Cordes

- Floors: 9

- Style: Classical Revival

- New York City Landmark: 1999

640 Broadway Recommended Reading

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report NOHO Historic District – page 50)

- The New York Times Habitats The Domestication of a Dive (February 12, 2010)

- Real Estate Weekly ‘Empire State Building’ sold for $32M (February 17, 2012)

- Forgotten New York blog

- Luxury Rentals Manhattan listing