256 Fifth Avenue is among the few examples of Moorish Revival architecture in New York City. As the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission noted, it’s “remarkably intact” for a building that went up in 1893.

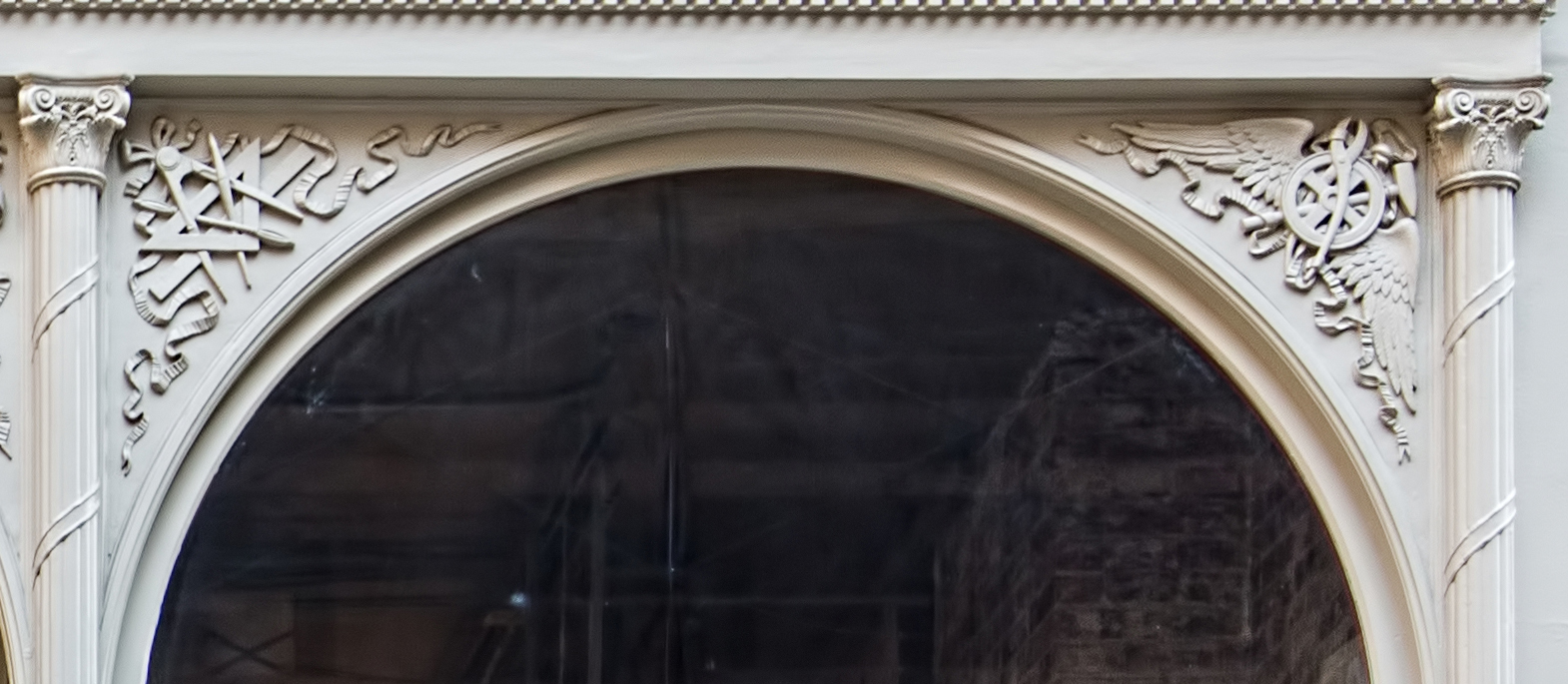

The windows steal the show: Their size, shape, number and decoration changes from floor to ornate floor.

Alas, the building is not without alterations. The ground floor storefront is now standard commercial granite; the sixth-floor terra cotta balcony was removed – probably because it was in danger of falling after a century of use. The gaps in the terra cotta were never filled in.

256 Fifth Avenue Vital Statistics

- Location: 256 Fifth Avenue between 28th and 29th Streets

- Year completed: 1893

- Architect: Alfred Zucker and John Edelman

- Floors: 6

- Style: Moorish Revival

- New York City Landmark: 2001 (Madison Square North Historic District)

256 Fifth Avenue Recommended Reading

- NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission designation report (pg. 86)

- Daytonian in Manhattan blog

- Street Easy NY listing

- Emporis database