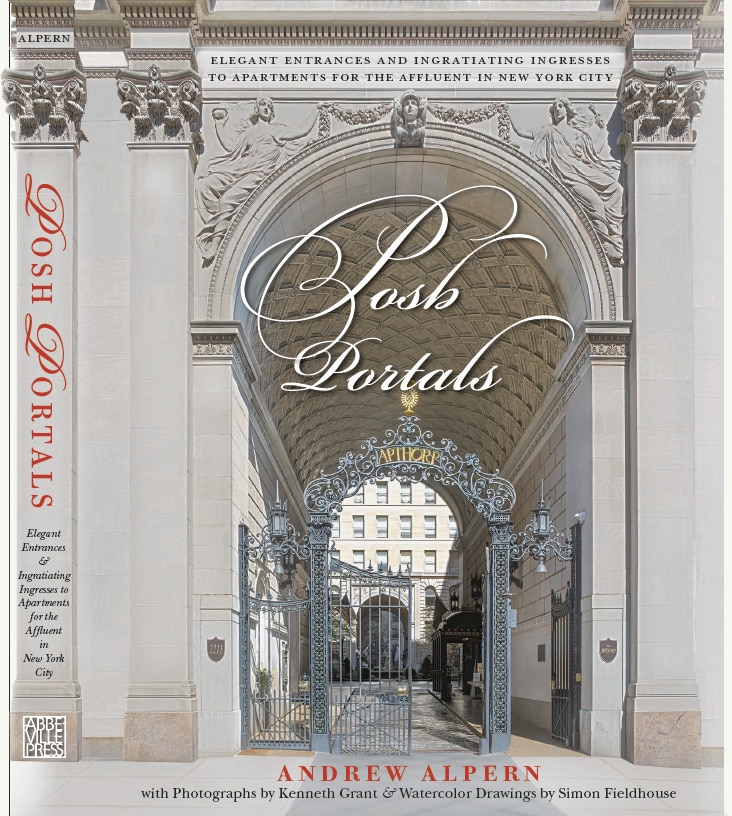

I’ve been calling Posh Portals “my book” for years, though actually the author is noted architectural historian Andrew Alpern – who already had 10 other volumes published. But the cover and more than 350 inside photos are mine, and the watercolor illustrations are also based on my photos, so I really can’t be too objective, can I?

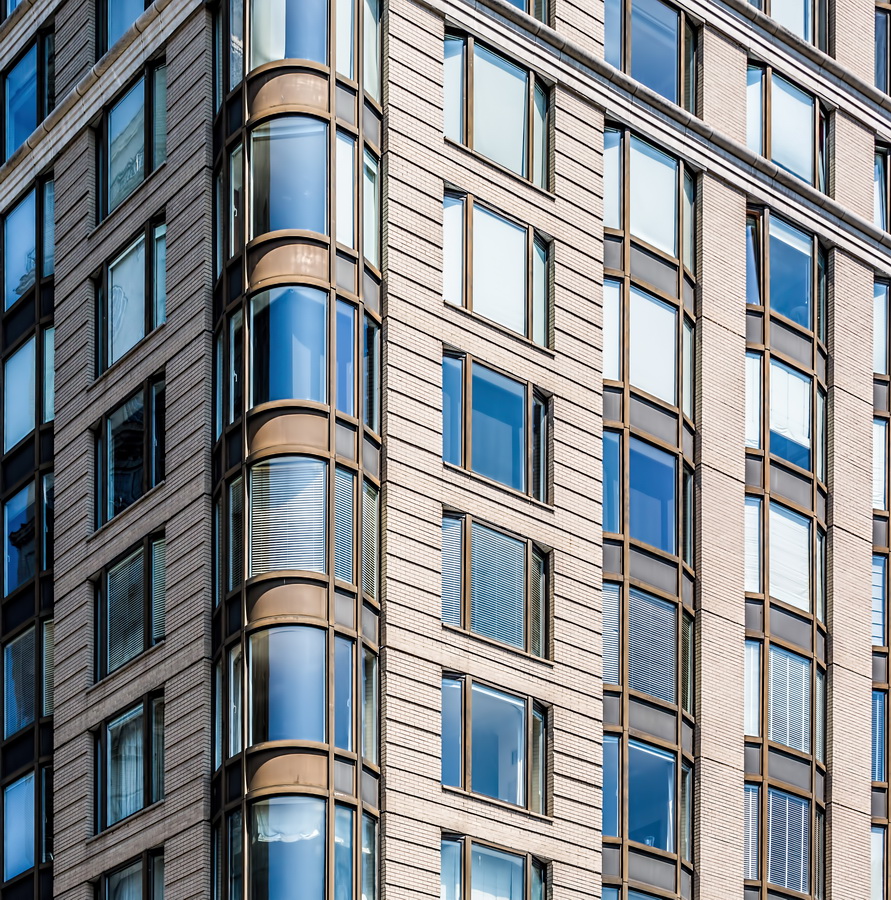

One of the reasons that I find architecture so fascinating is that buildings, like people, are so similar and at the same time infinitely diverse.

Take doors, for example. Every apartment building has to have a way in, obviously. It has to be substantial enough to keep out the elements, and large enough to permit occupants and their belongings to enter. So much for the similarities. The size, shape, material, style and embellishment, the scale, framing and placement of the front door are variables that together articulate the building’s character. A building’s portrait is never complete without an image of the front door.

In years of roaming cities with my camera, I’ve often shot doors and ignored the rest of the building. Some ancient, dilapidated dwellings – even crumbling tenements – were endowed with inviting portals. To the extent permitted by a developer’s budget, architects pride themselves on combining beauty with utility. One of the saddest parts of public housing is the cold steel front door, a mean, forbidding portal obviously designed more to keep people out than to invite people in.

In Andrew’s words, “The entrance to an apartment house is that important first impression, the opening sentence of the architectural story that sets the mood of the apartment building. A successful apartment house entrance must perform several functions, all of which must be kept in a delicate balance, consistent with the program that the developer has laid out for the architect to fulfill. The entrance is the dividing line between public and private space. It must make clear to the passer-by that he may approach and enter only if he has legitimate business within. Yet that entrance cannot be as forbidding as a fort, nor as evidently guarded as a prison, as it provides entrée to the homes of its residents, who may be the hosts of the approaching visitors.”

Here, then, is a collection of New York City’s most luxurious and distinctive apartment buildings, each endowed by their architect with entrances that speak volumes.

While these Posh Portals are no accident, my role this collection is definitely a case of serendipity. Your humble photographer was walking south along New York City’s Central Park West, an avenue lined with magnificent architecture. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed a distinguished-looking gentleman sitting on a bench across from the famed Dakota; there was something familiar about him . . . A few steps later it clicked: “Andrew?” I asked, approaching the bench. “Ken?” he replied. Until this morning, we had only seen photos of each other, though we had conversed almost five months about photos for his book, “The Dakota – A History of the World’s Best-Known Apartment Building.” He was waiting for a friend, and Andrew described a project he and Australian artist Simon Fieldhouse were discussing, an illustrated guide to the elaborate and ornate entrances to New York’s luxury apartment buildings. They’d need a good source of photos . . .

And so, from this chance meeting on a sunny January 13, 2014, my camera and I became part of Posh Portals. It’s been fun, educational, and sometimes challenging: Photographing buildings from street level in New York puts you at the mercy of the sun, traffic, parked trucks, and scaffolding that sometimes stays in place for years. The project took less than six minutes to describe, more than six years to complete, and was worth every second.

While obviously I’d LOVE for you to buy the book (shameless plug) from Amazon.com (as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases), photographs from Posh Portals are also available as framed or unframed prints on heavy paper, acrylic, or metal in a variety of sizes and styles. Just visit my Posh Portals photo gallery.

My gallery could not include the watercolor drawings by Simon Fieldhouse, but you can contact the artist at www.simonfieldhouse.com/new-york-apartment-entrances/.

Is your building here?

These are the notable apartment buildings we’ve selected as the Posh Portals of New York City. They’re listed by street address in dictionary order, so you’ll find 2 Sutton Place South after 1925 Seventh Avenue.

1 East End Avenue • 1 Fifth Avenue • 1 Sutton Place South • 1 West 30 Street – Wilbraham • 1 West 67 Street – Hotel des Artistes • 1 West 72 Street – Dakota • 10 Gracie Square • 1000 Park Avenue • 101 Central Park West • 1016 Fifth Avenue • 1067 Fifth Avenue • 1107 Fifth Avenue • 116 East 68 Street – Milan House • 1185 Park Avenue • 1198 Pacific Street – Imperial • 12 West 72 Street – Oliver Cromwell • 1215 Fifth Avenue • 1225 Park Avenue • 126 East 12 Street • 1261 Madison Avenue • 135 Central Park West – Langham • 135 East 79 Street • 135 West 70 Street – Pythian • 136 Waverly Place – Waverly • 140 Riverside Drive – Normandy • 141 East 3 Street – Ageloff Towers • 145 Central Park West – San Remo • 145 West 79 Street – Manchester House • 147 West 79 Street • 15 Central Park West • 15 West 67 Street – Central Park Studios • 151 Central Park West – Kenilworth • 171 West 71 Street – Dorilton • 180 West 58 Street – Alwyn Court • 19 East 72 Street • 1925 Seventh Avenue – Graham Court • 194 Riverside Drive

2 Sutton Place South • 20 East End Avenue • 200 Hicks Street -Casino Mansions Apartments • 201 West 79 Street – Lucerne • 210 East 68 Street • 2109 Broadway – Ansonia • 211 Central Park West – Beresford • 214 Riverside Drive – Chatillion • 215 West 98 Street – Gramont • 22 East 89 Street – Graham • 2207 Broadway – Apthorp • 222 Central Park South – Gainsborough • 225 Central Park West – Alden • 225 West 86 Street – Belnord • 235 East 22 Street – Gramercy House • 235 West End Avenue • 239 Central Park West • 240 East 79 Street • 241 Central Park West • 243 Riverside Drive – Cliff Dwelling • 243 West End Avenue • 246 East 4 Street • 25 Central Park West – Century • 25 East End Avenue • 251 West 71 Street • 25-35 Tennis Court – Chateau Frontenac • 258 Riverside Drive – Peter Stuyvesant • 27 West 67 Street – Sixty Seventh Street Studio • 285 Central Park West – St. Urban

3 East 84 Street • 30 East 76 Street • 300 Central Park West – Eldorado • 301 West 108 Street – Manhasset • 305 West 98 Street – Schuyler Arms • 310 Riverside Drive – Master Apartments • 32 St. Marks Place • 325 East 79 Street • 325 West End Avenue • 33 West 67 Street • 333 West End Avenue • 336 Central Park West • 34 Gramercy Park East – Gramercy • 344 West 72 Street – Chatsworth • 350 West 85 Street – Red House • 37 Washington Square West • 370 Central Park West • 380 Riverside Drive – Hendrik Hudson • 39 Fifth Avenue • 393 West End Avenue

40 East 62 Street • 400 Chambers Street – Tribeca Park • 401 Eighth Avenue Brooklyn – Roosevelt Arms • 410 Riverside Drive – Riverside Mansions • 418 Central Park West – Braender • 420 West End Avenue • 425 West 23 Street – London Terrace • 43 Fifth Avenue • 435 East 52 Street – River House • 439 East 551 Street – Beekman Mansion • 44 West 77 Street • 440 Riverside Drive – Paterno • 440 West End Avenue • 444 Central Park West • 446 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn • 45 East 66 Street • 450 East 52 Street – Campanile • 455 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn • 465 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn • 47 Plaza Street • 480 Park Avenue • 488 Nostrand Avenue – Renaissance • 49 East 96 Street • 490 West End Avenue • 495 West End Avenue • 498 West End Avenue

50 Central Park West – Prasada • 509 East 77 Street – Cherokee Apartments • 509 West 121 Street – Bancroft • 515 Park Avenue • 52 Riverside Drive • 520 Park Avenue • 521 Park Avenue • 522 West End Avenue • 527 Cathedral Parkway – Britannia • 540 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn – Cathedral Arms • 55 Central Park West • 57 West 75 Street – La Rochelle

625 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn – Arista • 666 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn – Cameo Court

7 Gracie Square • 70 Remsen Street • 70 Vestry Street • 711 Brightwater Court • 716 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn – Valence • 720 Park Avenue • 726 Ocean Avenue Brooklyn • 730 Park Avenue • 74 East 79 Street • 740 Park Avenue • 770 Park Avenue • 780 West End Avenue

800 Park Avenue • 820 Park Avenue • 834 Fifth Avenue • 838 West End Avenue • 850 Park Avenue • 898 Park Avenue

924 West End Avenue – Clebourne • 993 Fifth Avenue • 998 Fifth Avenue

You must be logged in to post a comment.