Highlights from photos shot in May, 2014 – but not yet added to a New York neighborhood or specific building gallery. Mostly architecture, some whimsical, all except the last five in Lower Manhattan; the last five (Prada entrance) are from the Upper East Side.

These were all taken May 17, 18 & 20, while I was shooting residential buildings.

I started out in Chinatown, walked to the East River, then down to the Battery. I used the Staten Island Ferry Terminal as a viewpoint for some of the photos, and gathered the rest while walking up Broadway; the last five (Prada entrance) I spotted while walking down Madison Avenue.

Enjoy!

In this album:

- 202 Centre Street

- Takin’ his Chevy to the levee…

- Mulberry Street fire escape

- Mott Street

- God Bless America, Land of Firearms

- Brooklyn Heights

- Sheriff’s car at Wall Street Heliport

- Governor’s Island Ferry Terminal

- Governor’s Island Ferry Terminal

- 20 West Street

- 33 & 3 – 33 Whitehall Street and 3 NY Plaza

- 33 & 3 – 33 Whitehall Street and 3 NY Plaza

- 33 & 3 – 33 Whitehall Street and 3 NY Plaza

- Custom Reflection

- Trinity Church

- 2 Rector Street

- 40 Wall Street (Trump Building)

- Old & New

- Old & New

- Detail: Europe (Alexander Hamilton US Custom House)

- Trinity Building cupola

- 29 Broadway

- 2 Rector Street

- Trinity Building cupola

- Trinity Church

- Trinity Building entrance

- Trinity Building entrance

- United States Realty Building entrance

- Park Row Building – north tower

- Surrogate’s Court

- Surrogate’s Court

- Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank Building

- A Six Park

- Batty

- Smoker

- Blue

- Purple

- Who Me?

- Pair of Hooters

- Brass Bird

- Brass Bird

- Grace Church detail

- Grace Church detail

- 808 Broadway

- Roosevelt Building

- Clock. Tower.

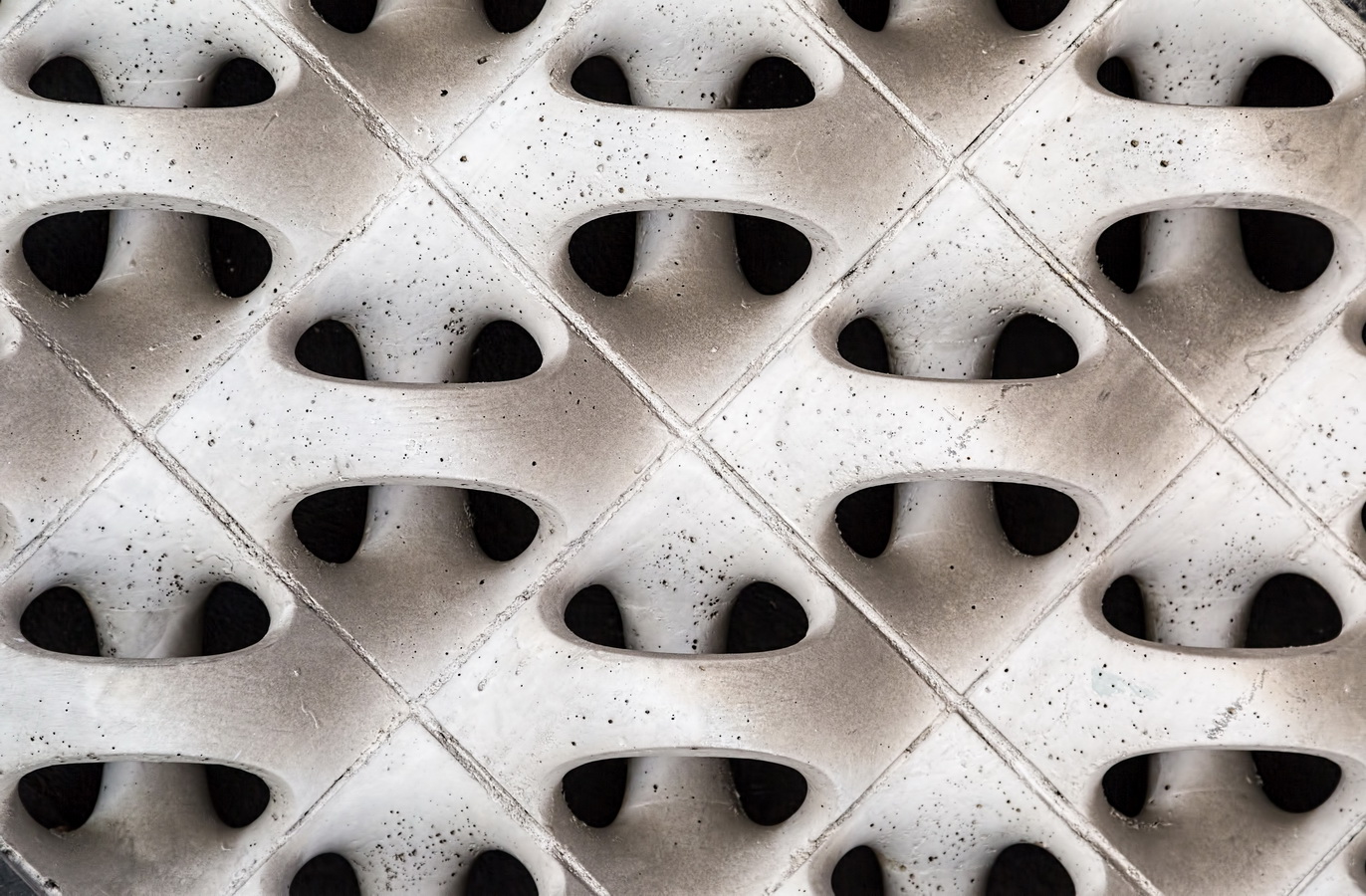

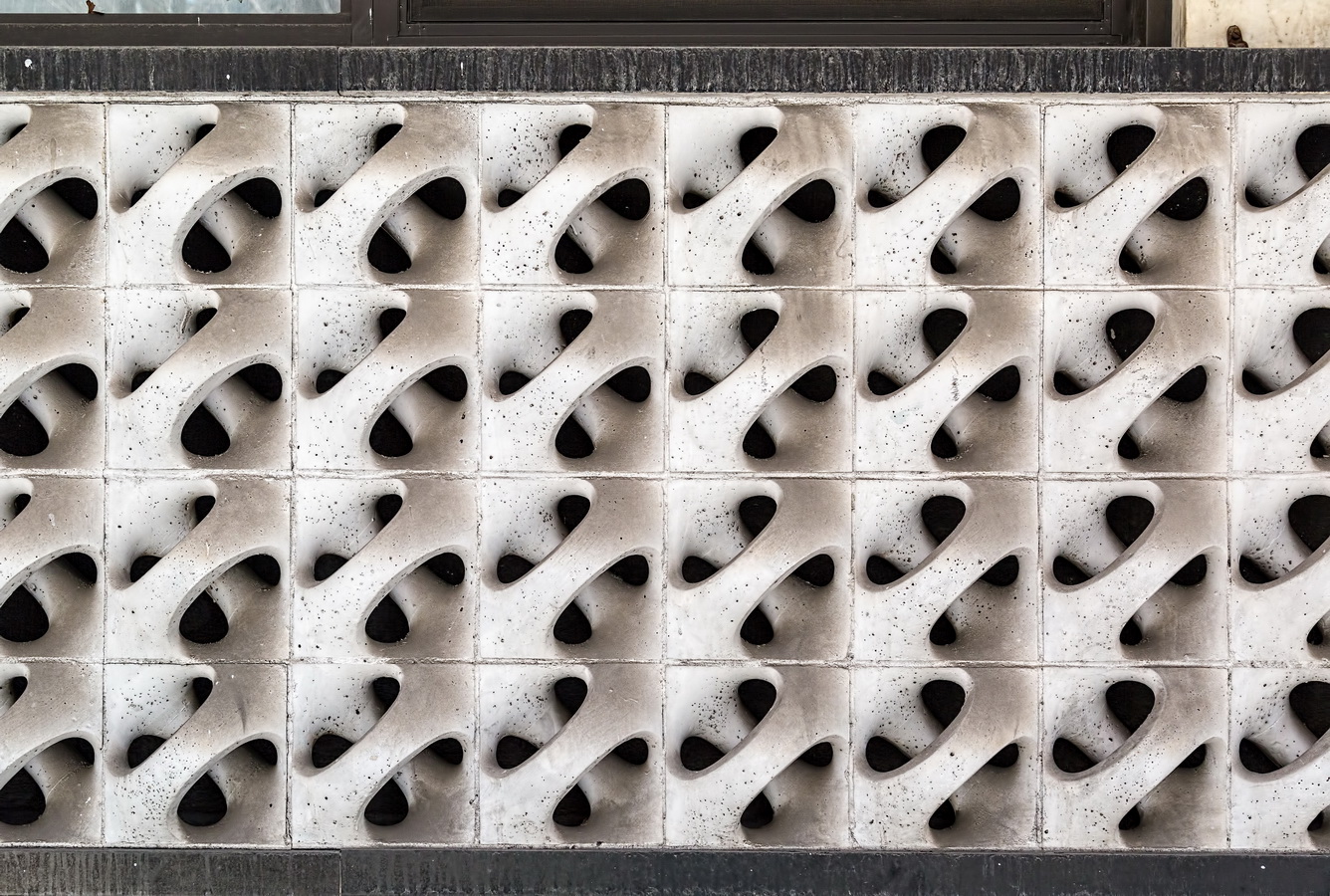

- Entry detail [1]: Prada store, 841 Madison Avenue at E 70th Street

- Entry detail [2]: Prada store, 841 Madison Avenue at E 70th Street

- Entry detail [3]: Prada store, 841 Madison Avenue at E 70th Street

- Entry detail [4]: Prada store, 841 Madison Avenue at E 70th Street

- Entry detail [5]: Prada store, 841 Madison Avenue at E 70th Street

![Entry detail: Prada store [2] Entry detail: Prada store [2]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8638_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [1] Entry detail: Prada store [1]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8640_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [3] Entry detail: Prada store [3]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8646_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [4] Entry detail: Prada store [4]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8648_resize.jpg)

![Entry detail: Prada store [5] Entry detail: Prada store [5]](https://www.newyorkitecture.com/wp-content/gallery/random-may-2014/NO5A8649_resize.jpg)