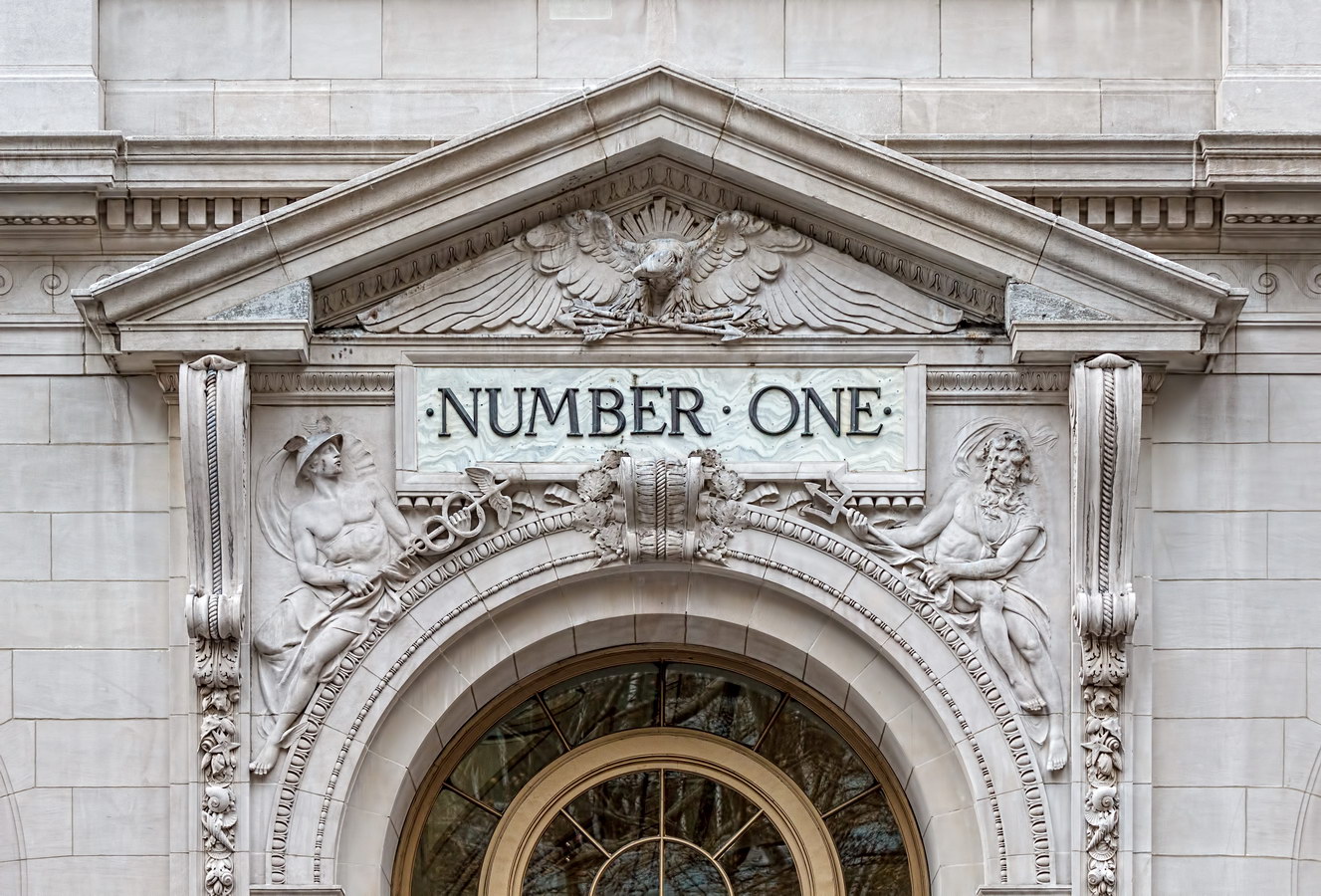

Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is one of New York City’s most important landmarks, both for its history and for its architecture.

Historically, this is the site of New York’s first Custom House; the first building burned down. The choice of architect was the first major use of the 1893 Tarnsey Act, which allowed private architects to design public buildings. Cass Gilbert won the commission, after heated (and controversial) competition. The United States Custom House also served as a test of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission: In 1965 the then-new agency was designating a federal building as a city landmark, and the regional administrator for the General Services Administration (GSA) argued that the city had no authority to regulate federal property. (Nonetheless, the city returned in 1979 to declare the interior as a landmark!)

The building was hugely important to the nation: Import duties charged here and at other ports financed the government, in the days before an income tax. The Customs Service moved to the World Trade Center in 1971. The building was empty for a decade, and slated for demolition until Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D, NY) sponsored a bill to restore the Custom House. Additional legislation required the GSA to find new uses for unused federal buildings (they needed a law to figure that out?). Now, the building is shared by the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, the National Archives, and the National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian Institution).

You can’t tell it from these photos, but the Custom House is actually trapezoidal: The back of the building is wider than the front.

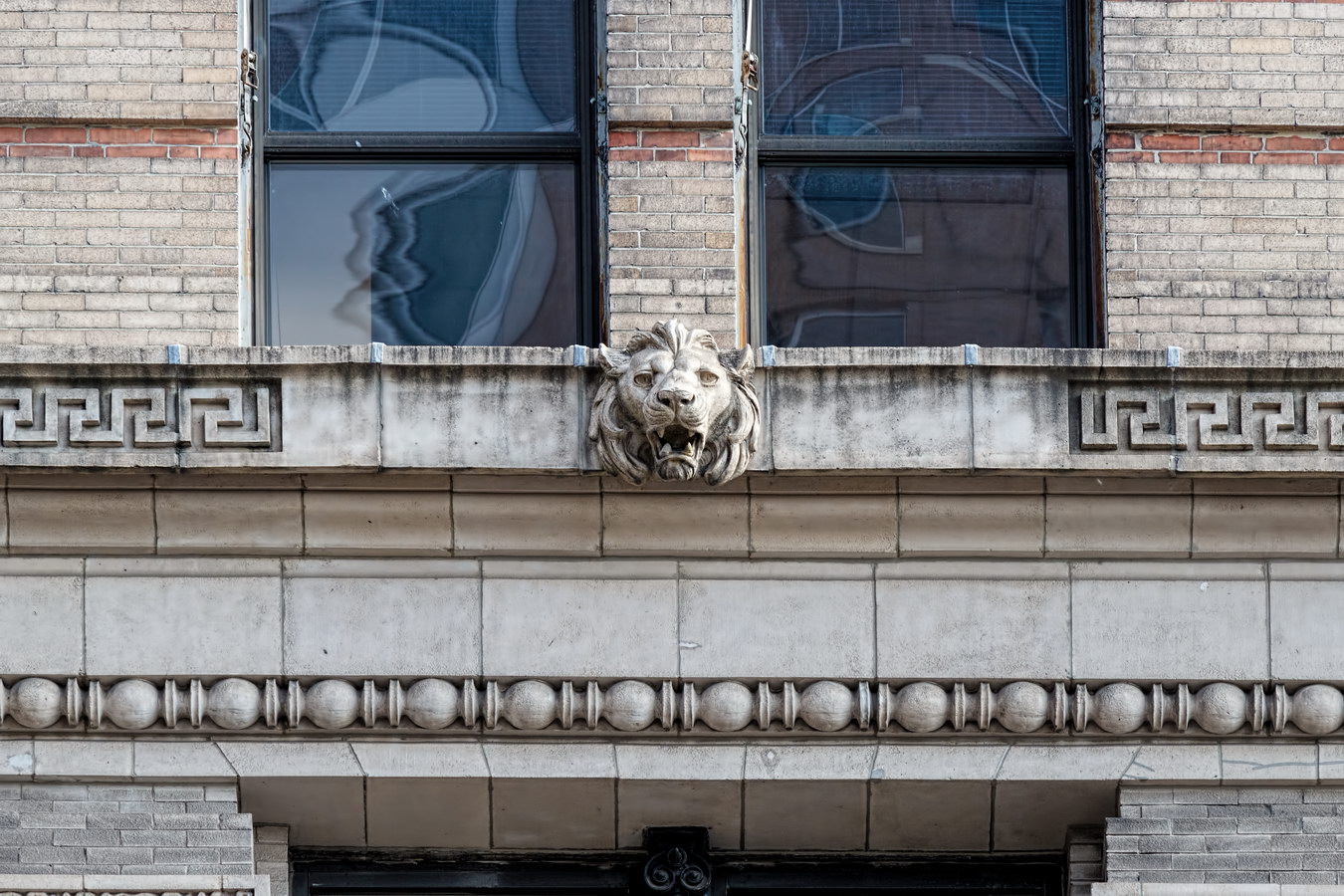

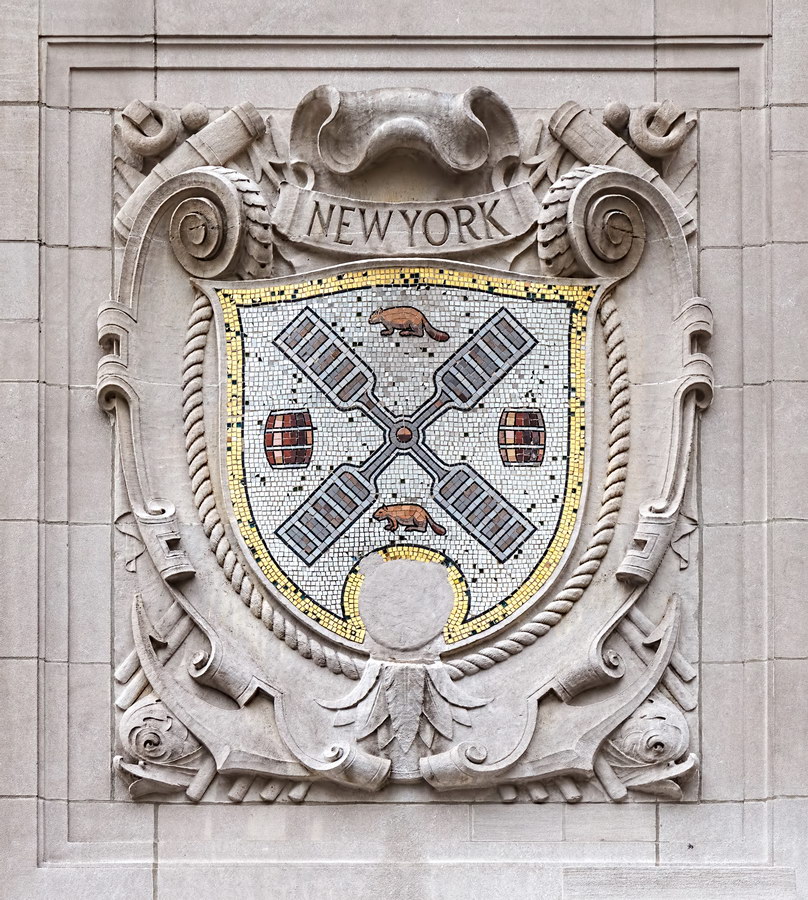

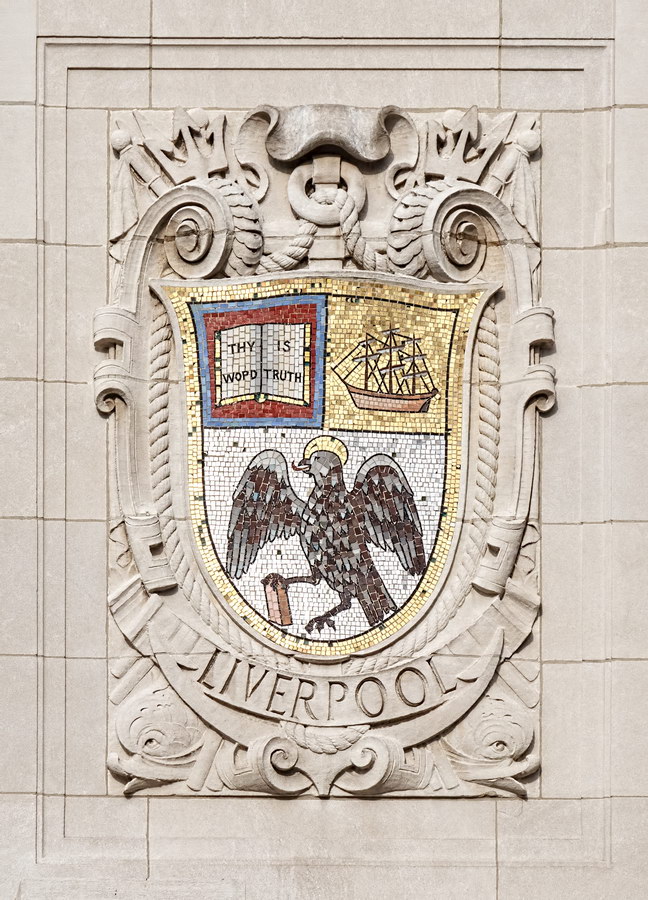

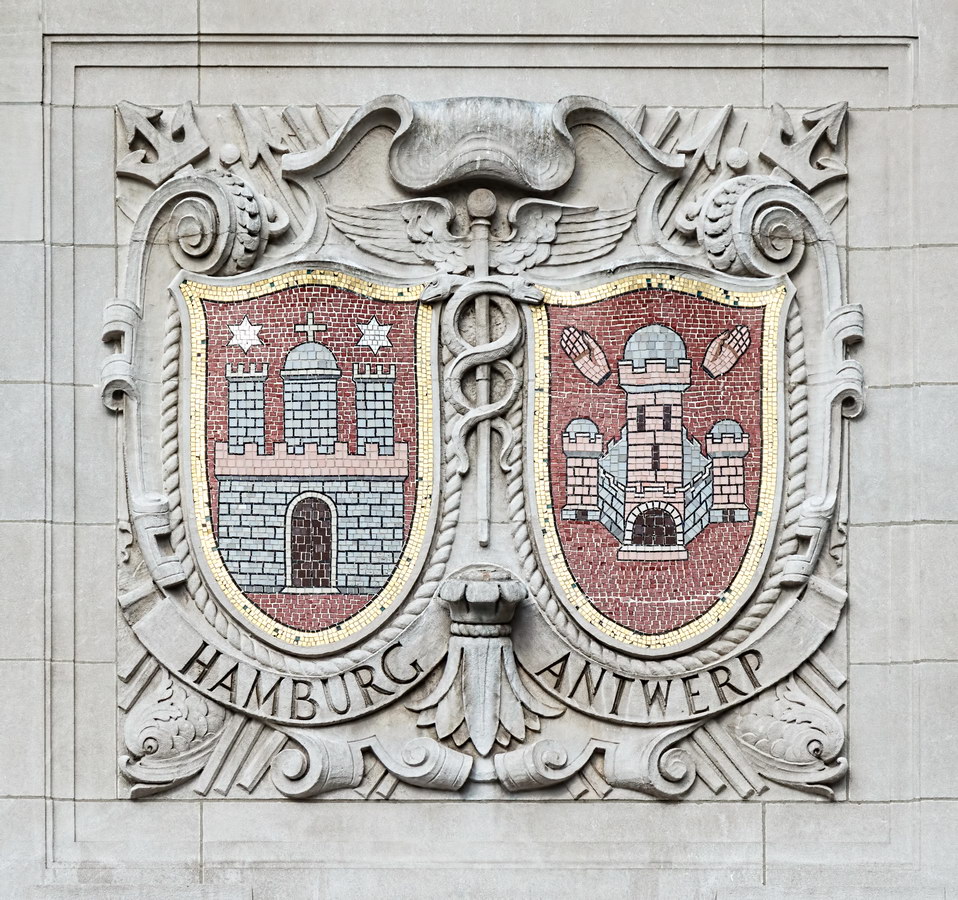

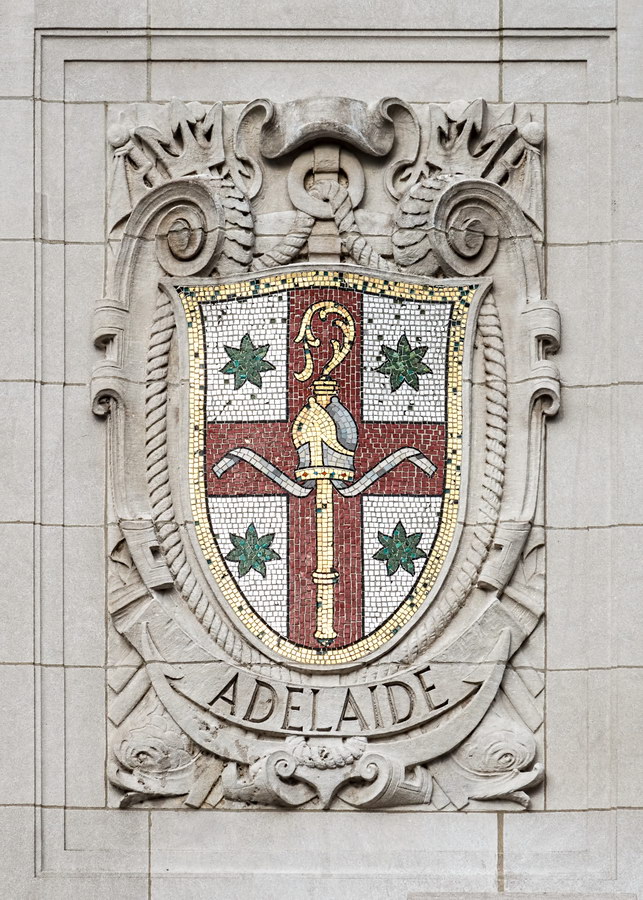

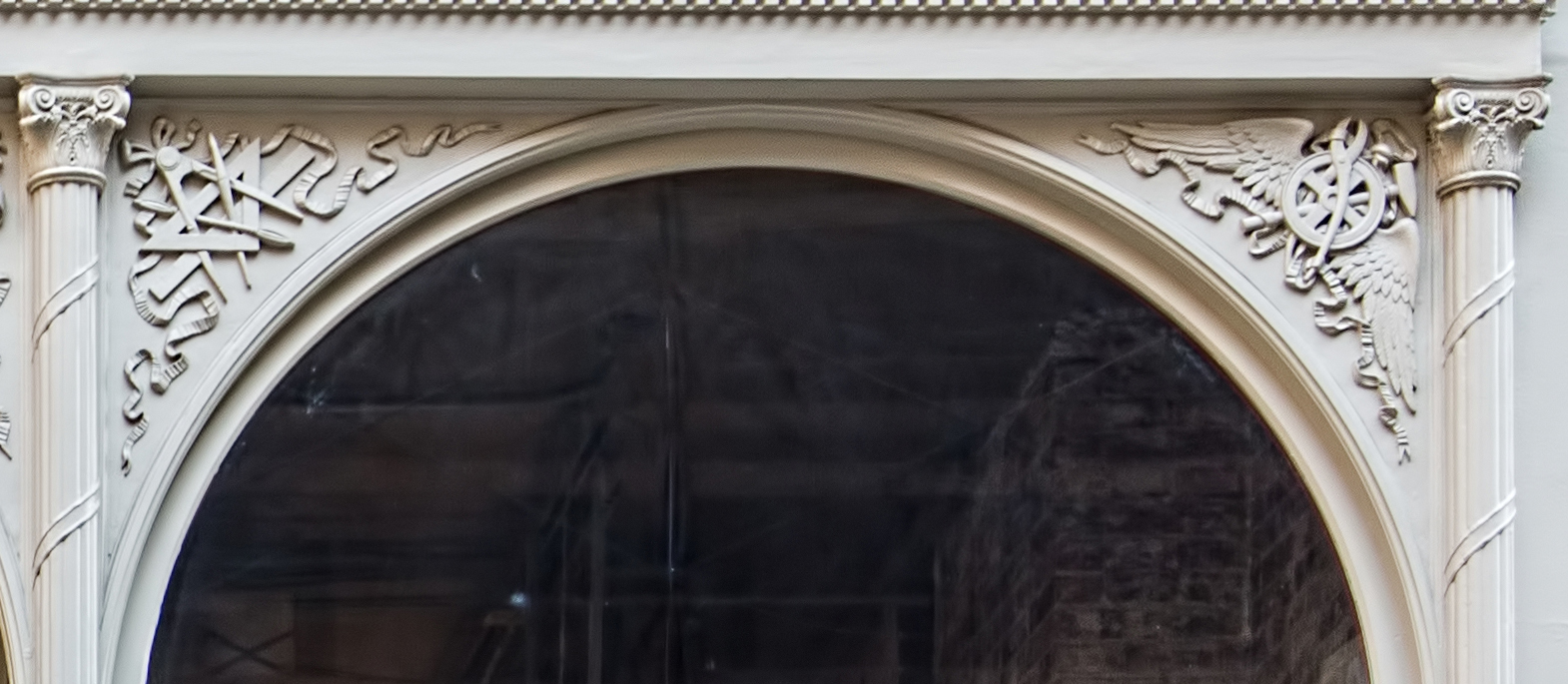

Cass Gilbert’s Beaux Arts design is filled with symbolism and references to classical architecture. The four monumental sculptures in front of the building, sculpted by Daniel Chester French, represent the continents Asia, Africa, America, and Europe. Statues representing 12 seafaring nations stand above the front facade’s columns; the Corinthian capitals of the columns include the head of Mercury (representing commerce); second-story windows are topped by heads representing the “eight races of mankind.”

How did Belgium wind up among the top 12 seafaring nations? According to “Secret New York, An Unusual Guide,” the statue was originally Germany, but ordered changed after the outbreak of World War I.

Interior details are equally rich (and also designated a New York City Landmark). New York artist Reginald Marsh painted the murals in the second floor rotunda, as part of a Treasury Relief Art Project (an offspring of the W.P.A.) in 1937.

(The GSA has an extensive photo gallery showing interior details.)

Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House Vital Statistics

- Location: Bowling Green

- Year completed: 1907

- Architect: Cass Gilbert

- Floors: 7

- Style: Beaux Arts

- New York City Landmark: 1965, 1979

- National Register of Historic Places: 1972

Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House Recommended Reading

Google Map